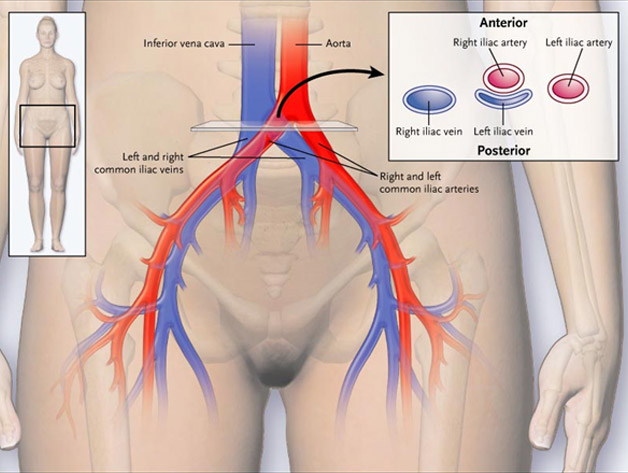

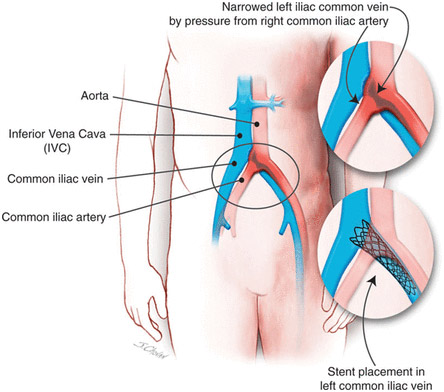

People can have narrowing of a vein for several reasons. One of them is an anatomic variation called May-Thurner syndrome. In normal anatomy, the artery leading to the right leg (called the right common iliac artery) rests on top of the vein coming from the left leg (the left common iliac vein). In some people, the artery puts increased pressure on the vein, causing the vein to be narrowed (Figure 2). People are born with this variant and have it throughout their life. The narrowing can range from mild to severe. Some studies estimate that 20% of people have some degree of narrowing. Severe narrowing is less common. Veins can also become chronically narrowed as a result of scarring from previous DVTs or from external compression (eg, from a cancer). Significant narrowing can lead to blood flow disturbance and can increase the chance of developing a DVT.

Most people with May-Thurner syndrome have no symptoms and will never develop any. Even if the vein is severely narrowed, bypassing veins (collaterals) may open up and drain the leg so that a patient may be without symptoms. However, in some people, the narrowing can lead to chronic leg swelling or can contribute to the formation of a DVT in the left leg.

A routine Doppler ultrasound of the leg is not likely to see the narrowing because the veins involved are deep in the pelvis, an area that a Doppler ultrasound cannot visualize. A computed tomography venogram or magnetic resonance venogram of the pelvis can show the narrowing of the vein. Another way to see the narrowing is by injecting contrast dye into a vein in the leg, called a contrast venogram. Sometimes, intravenous ultrasound is done with an ultrasound catheter in the vein. This is to determine the degree of narrowing and to measure pressures in front of and behind the narrowed stretch of vein to determine how severely narrowed the vein is.

It is unknown how much the vein narrowing increases the risk for developing a DVT. DVTs are often attributable to multiple risk factors, not just one. May-Thurner syndrome may contribute to DVT. However, it is important to determine other risk factors (major surgery, major trauma, hospitalization or other immobility, long-distance travel, birth control pill, patch or ring, pregnancy, etc) and perhaps to assess for congenital or acquired clotting disorders by blood testing before blaming the occurrence of a DVT on the presence of May-Thurner syndrome.

- Vein stents are not indicated in people who have no symptoms and have not had a DVT.

- Vein stents are not indicated in people who have no symptoms and have not had a DVT.

- People with a DVT in the leg who are found to have significant May-Thurner syndrome can be considered for a stent. However, it is unknown if placing a stent decreases the risk of getting a blood clot in the future.

- A stent can be considered in the patient with May-Thurner syndrome who has had a DVT and who still has significant leg pain or swelling after a few months of blood thinner treatment. Studies have shown that leg symptoms may improve after stent placement.

A stent is placed with the help of a catheter via the large veins in the leg behind the knee or in the groin, with deployment of the stent in the area of narrowing. Most stents are patent for the first 1 to 2 years after being inserted.4 Unfortunately, some become narrowed within 3 to 5 years. When stents become narrowed, leg swelling may increase. A radiologist, vascular surgeon, or interventional cardiologist can put a catheter through the vein in the leg and open up the stent by using a balloon to reinflate the stent or by placing a new stent. This is usually successful.

If you have a stent and develop more leg swelling, leg pain, or a new DVT, then the radiologist, surgeon, or cardiologist should evaluate whether your stent is patent by injecting contrast dye into the veins of the leg. It is not known whether people with stents who are doing well and have no new symptoms need regular routine follow-up monitoring with images (such as a computed tomography venogram).

Once the stent is placed, you will likely stay on blood thinner medications for at least 3 months to treat your acute DVT. The decision on how long to treat with a blood thinner is based on the circumstances of the blood clot, your risk of bleeding, and how well you tolerate the blood thinner. If the blood thinner is stopped, we do not know if you should start on an antiplatelet medication (eg, aspirin or clopidogrel) because it is not known whether antiplatelets are beneficial in keeping vein stents open.